I didn’t discover Maurice Sendak’s book Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life till my late 30s, but count it among my favorites. Published in 1967 and dedicated to Sendak’s sealyham terrier, Jennie, Higglety Pigglety Pop! chronicles the adventures of Jennie the dog, who leaves home because “there must be more to life.”

I re-read the book last night and was surprised to remember how terrifying it is.

Jennie becomes nurse to Baby, who refuses to eat.

A nurse gets just one chance to feed Baby, and if she fails, the nurse is eaten up by the downstairs lion.

Jennie calls Baby’s parents, who left Baby behind when they moved to Castle Yonder.

Baby’s mother explains, “[W]ith all the hustling and bustling we forgot our old address and phone number and just didn’t know how to get in touch.”

Jennie asks how she should send Baby back to her parents:

“By lion,” said the lady. “There is one in the cellar and he knows the way.”

Jennie shivered. “Did you know that lion has eaten up six nurses and I don’t know how many babies?”

“Tell him Baby’s name and he won’t dare eat her.”

“What is Baby’s name? And what about me?”

There was no answer.

“Hello? Hello?”

It was no use. The lady had hung up.

What a horrifying rendition of childhood. Not only have Baby’s parents abandoned her, but they hardly seemed to notice she was gone. Baby’s Nurse is a hungry terrier who ate all the breakfast. And the only way for Baby to get back to her parents is by lion. Her mom and dad can’t even be bothered to give the nurse proper instructions to make sure Baby isn’t eaten on the way home. And this is not the cordial, pretty lion of Pierre, Who Didn’t Care – who is scary enough in his own right – but a fanged, ferocious beast.

When I nibble my two-year-old daughter’s foot, she giggles and scolds, “No, don’t eat me.” Re-reading Higglety, it dawns on me that she understands this game in a very different way than I do. I just like to hold her in my arms and make her squeal. But she is seeking daily confirmation that I am not, in fact, going to eat her. If I nibble her foot with my teeth, she admonishes, “No, pretend!” When I nibble with my lips, she relaxes, “That’s better.” So for her there are levels of pretending. Teeth are “real” pretending, and too scary. Lips are pretend pretending, and safer. “My God,” I think. “I gnashed my terrible teeth.” Sure enough, my daughter said, “Be still!”

Sendak had a direct access to the deepest fears of childhood and a gift for translating them to stories in a way that makes profound emotional sense to children.

In many ways, these fears transcend childhood to echo through our adult lives, for they are not merely children’s fears, but human fears.

In one way or another, don’t we all fear being devoured?

In her

New York Times obituary for Sendak, Margalit Fox captured Sendak’s knack for trusting children’s perspectives, noting his respect for “the essential rightness of children’s perceptions of the world around them.” How I love and admire that trust and aspire to let it guide my own work.

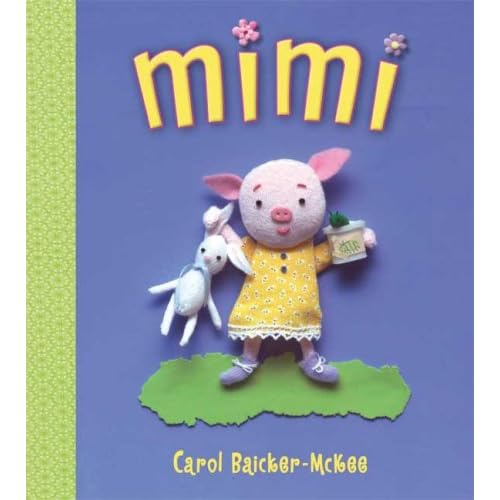

Reflecting on Sendak’s gift for channeling children’s fears helps remind me why we do this, why we devote ourselves to writing for children, why Saturday night at the Metz house looks like this:

Bruno Bettelheim wrote that for a story to enrich a child’s life, it must “stimulate his imagination; help him to develop his intellect and clarify his emotions; be attuned to his anxieties and aspirations; give full recognition to his difficulties, while at the same time suggesting solutions to the problems which perturb him…giving full credence to the seriousness of the child’s predicament.”

What could be more a more serious predicament than being abandoned by your parents and left in the cellar, staring into a lion’s gaping jaws? Maurice Sendak was deftly attuned to children’s anxieties and treated them with the respect and seriousness and imagination they deserve.

In Higglety Pigglety Pop!, Sendak’s dog Jennie mused that there must be more to life than having everything or having nothing. There is. There is the possibility, however fleeting, of enriching one another’s lives, through writing or drawing or cooking or laughing or talking or, like Pierre, simply caring.

Thank you, Mr. Sendak, for enriching all of our lives.